Previously, color matter derived from kohl, berries, tree bark, minerals, insects, herbs, and plants was commonly used as hair dye and tattoo material.

Early mummies discovered in Egypt had extensive Tattoos on female bodies, leading to many theories about their purpose.

Female figurine from the Naszca culture with a tattooed design on her lower torso, likely belonging to someone of high status.

The Iceman

Tattooing was already practiced in ancient Egypt, though its modern forms may have existed more commonly and widely.

Otzi, an Ice Cap Skeleton preserved 5,200 years ago, was found with small markings above joints and areas of tension that researchers have compared to acupuncture points.

Otzi was covered with 57 tiny tattoos, many located near acupuncture points. Pabst believes these markings were therapeutic rather than decorative, similar to how modern-day acupuncture works today and how pain relief from regular but intensive treatments works today.

His body also featured several herbal infusions, which may have been applied over his skin as marks; perhaps these treatments included those meant to treat ailments like arthritis.

Scythian Pazryk

Scythian culture flourished across Central Asia from the 6th to 2nd centuries BCE, becoming famous for their distinctive burial mounds (kurgans) and petroglyphs.

Mummies from this culture have become internationally renowned for the Tattoos on some of their women.

One woman, in particular, is known for having a particularly striking piece dubbed “Ice Maiden” that features multiple animals.

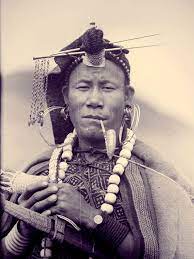

Nomadic people were once an influential force. One theory suggests they may have introduced tattooing practices from Siberia into Eastern Europe.

Georges Charriere wrote an excellent book titled, “Scythian Art: Crafts of Early Eurasian Nomads” on this subject; its contents include numerous Pazyryk archaeological finds and drawings and photos that beautifully document this history.

China

Ancient Chinese texts demonstrate that body marking was widespread; for instance, Youyang Zazu describes voluntary decorative Tattoos worn by both women and men from then on.

Yet before this point, Tattoos had an unpleasant cultural stigmatism – as criminals, military deserters, and prostitutes all used them to identify themselves.

Tattoos could also serve a medical function similar to Otzi. Based on their placement on the mummy, Tattoos may have been applied in certain areas to ease stress relief or relieve strain in certain regions.

Plutarch reports that Histiaeus of Miletus ordered one of his slaves to have their head shaven and tattooed with the name of Aristagoras as an attempt at inciting rebellion against Histiaeus’ rule.

Egypt

Middle Kingdom period Egyptian mummies (2160-1994 BCE) have revealed tattooed dot clusters on women that appear around their stomachs, thighs, and breasts; these markings protected pregnancy and childbirth.

Tattoos may also serve as a form of medicine; their patterns often mirror where strain exists in joints, suggesting they could help ease discomfort associated with certain conditions.

Different cultures across history have long used tattoos. Ancient Greek and Roman art featured tattooed slaves, while the Scythian Pazyryk people called these marks “stigmata.”

Tattoos were typically used to identify lower-status individuals or deter them from returning to society should they escape slavery. Tattooing later spread with migration and expansion of empires, with Greek and Roman authors writing extensively about it.