At Cook’s expedition, many of his sailors received Tattoos as part of a tradition within the navy. Enlistment papers even recorded these designs as an element of service.

Early English tattoos

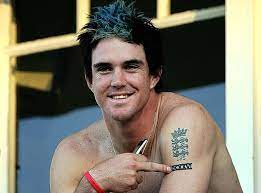

Early English Tattoos were an increasingly popular means to express personal beliefs and heritage, often using Anglo-Saxon symbols such as lions, eagles, and other animals that symbolized strength and courage as symbols on one’s skin.

As the 19th century progressed, tattooing in England became more widespread. Tattooists established shops and sold tattoo kits that allowed individuals to self-ink themselves. These kits included needle and ink, stencils, and aftercare instructions.

One of the most prevalent designs was a dot. Being simple to draw, sailors and convicts used these dots to signify good fortune – even wealthy individuals would get them done.

Tattoos were also inspired by historical events or places, like the Sutton Hoo tomb, which showed an image of the Anglo-Saxon god Tiw – venerated by warriors for inspiring courage – who also is responsible for many place names throughout England.

Early British tattoo artists

Tattooing was widely practiced among soldiers during World War 2, especially during its later stages. Soldiers would wear flags or military crests alongside sweethearts’ names; portraits of public figures would adorn themselves; foreign allied troops provided an additional customer base for many tattoo shops.

Captain James Cook introduced body art to Britain with his voyages to Tahitian Islands. Seamen soon followed suit, and tattooing quickly became more prevalent throughout British ports by the second half of the 19th century – becoming a widely accepted form of identification for many individuals.

Tom Riley and Sutherland Macdonald were two early British tattoo artists who gained prominence during this era. Both served in the military – Riley in the Boer War and the Sudan Campaign of the African War, while Macdonald served in the British army in the 1880s – and their tattoo designs were intricate and colorful, often using traditional elements and innovations.

Early British military tattoos

Military Tattoos serve as an unbreakable reminder of long lives lived and short deaths endured by soldiers, as well as the courage and loss experienced throughout their service careers. A joint exhibition by the Royal British Legion and National Memorial Arboretum explores their power.

Tattooing was traditionally introduced to Europe during Captain Cook’s voyages to Polynesian islands, yet historians have discovered evidence that sailors had already been tattooed long before this. Tattooing was an English translation of the Tahitian phrase tatau used as a visual signifier. Specific patterns or designs used for warriors and rowers were inked onto sailors long before this.

In the Victorian era, tattooing gained new audiences, such as upper-class members and members of royalty (Prince George was often photographed wearing one). Tom Riley and Sutherland Macdonald served in the army during this era, where they refined their skills by marking soldiers with regimental crests or other designs; after leaving, they opened tattoo parlors while mentoring young sailors like George Burchett (later to become one of Britain’s premier naval tattoo artists).

Modern British military tattoos

Tattoos have become more widespread within modern British society, and many service personnel proudly wear them as part of their uniform. Tattoo artists can often be found in garrison towns, where they play an essential role in community life; some specialize in producing customized designs tailored specifically to each serviceman or woman they create unique artwork for.

Charlie Clift, an award-winning photographer known for his military photography work, was given access to a diverse array of military-inspired locations ranging from aircraft hangars and decks of Royal Navy ships – telling stories of long lives lived, swift deaths endured, and acts of heroism as well as tragic sacrifice. The resultant images tell these narratives.

The Tattoo brings together Armed Forces from around the globe and volunteers civilian performers for an extraordinary month-long experience that promotes greater trust between allies and potential foes – its motto being: ‘Let nations speak peace unto nations”.